Dancers wheeled by in a fluid blur of colors and feathers to chanting and singing so moving it reached down into the body, grabbed the insides and gave ‘em a shake so that even those who didn’t understand the words could feel their power.

At heart of the Muckleshoot Tribe Pow Wow last Friday and Saturday at Olympic Middle School – indeed, at the heart of any pow wow – was the host drum’s beat, a thump! thump, thump! that set the feet in motion and lifted spectators up before setting them down again with a healthy whack.

“The drum beat itself is the core of the whole thing, like the human heart that keeps beating,” said Dr. Kelvin Rank, a member of the plains Cree tribe from Saskatchewan who works for the planning department of the Muckleshoot Tribe. “Without the drum, we wouldn’t have this.”

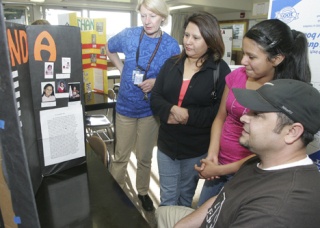

Last week’s pow wow, open to all, brought together members of the Muckleshoot Tribe, native Americans as far east as Oklahoma, and the Red Tail Drumming group from Lapwai, Idaho. It was held in conjunction with the school’s annual cultural fair, “Celebrate Us.”

In an age of cell phones and computers, the Pow Wow links Native Americans back to their vital roots and culture.

A pow-wow – reportedly derived from the Algonquian “powwaw,” meaning “spiritual leader” – brings Native American and non-Native American people together to dance, socialize, sing and honor their culture.

“The pow wow itself is a celebration of life through sharing of our songs and our dances,” Rank said. “We just go out and have a good time, and everybody gets to share their songs from different tribes throughout the nation with different styles of dancing from south to north, from east to west. Today it’s mainly used as a healing process, whether you’re ailing or you have someone up there who is sick. It’s actually a spiritual circle. It’s just the way we do things when we try to heal.”

Pow-wows vary in length from one day session of five to 6 hours to three day. Major pow-wows can be up to one week long.

“It’s a little celebration that is open to the public,” Rank added. “It’s just a way that we share a portion of our culture, the way we sing, the way we dance so people can hear them and enjoy them. We hope that we can reach deep into their hearts as a way of healing.

“I had tears running down my eyes when the host was singing a powerful song. It took me back to my late father, who was a leader of his community for many, many years, just thinking about him,” Rank said.

The master of ceremonies was Yakama Tribal member Jerry Meninick. The host drum sang songs chosen by the Pow Wow Committee.