As recently as one month ago, Multicare Auburn Medical Center was tending an average of 5 to 7 COVID-19 patients each day.

By last Friday, however, that number had hit a daily 20 patients, a 50 percent increase in four weeks, said Arun Matthews, Chief Medical Officer for MAMC and for Multicare Covington Medical Center.

But when Matthews looks about the hospital these days, he finds himself thinking not so much about hardships, but of everything that MAMC and the community have to be thankful for in this crisis.

For critical renovations fortuitously completed just as the pandemic broke, especially the opening of the new emergency department,which has allowed MAMC to meet the community’s need in this time.. Of a 30-day supply of N-95 respirators, and a 90-day supply of masks and gloves and gowns.

“I am just so grateful that some of those things have been put into place, because COVID-19, at the local community, regional and national levels, is really testing and bringing out the very best in us,” Matthews said.

“But, man,” Matthews added, with an exhalation of breath, “it’s been a long haul, and it continues to be a long haul.”

Throughout the state, as of Saturday, there was a record 762 people receiving care for the virus, and like its sister hospitals, MAMC is working on ways to keep beds available.

In the grand scheme of things, MAMC’s average daily census falls between 80 and 100 patients, with a bit of remaining capacity to take on more, based on need.

“I wouldn’t say we are overrun, that every single bed is inhabited by a COVID-19 patient, but we are seeing a substantive increase of patients coming to be assessed, with a percentage of those being sick enough to be admitted to the hospital. The interesting thing is that, as we learn how to manage COVID-19, we recognize that there are patients who test positive, but they have mild symptoms, and they can actually go back home and convalesce and self-quarantine safely. “

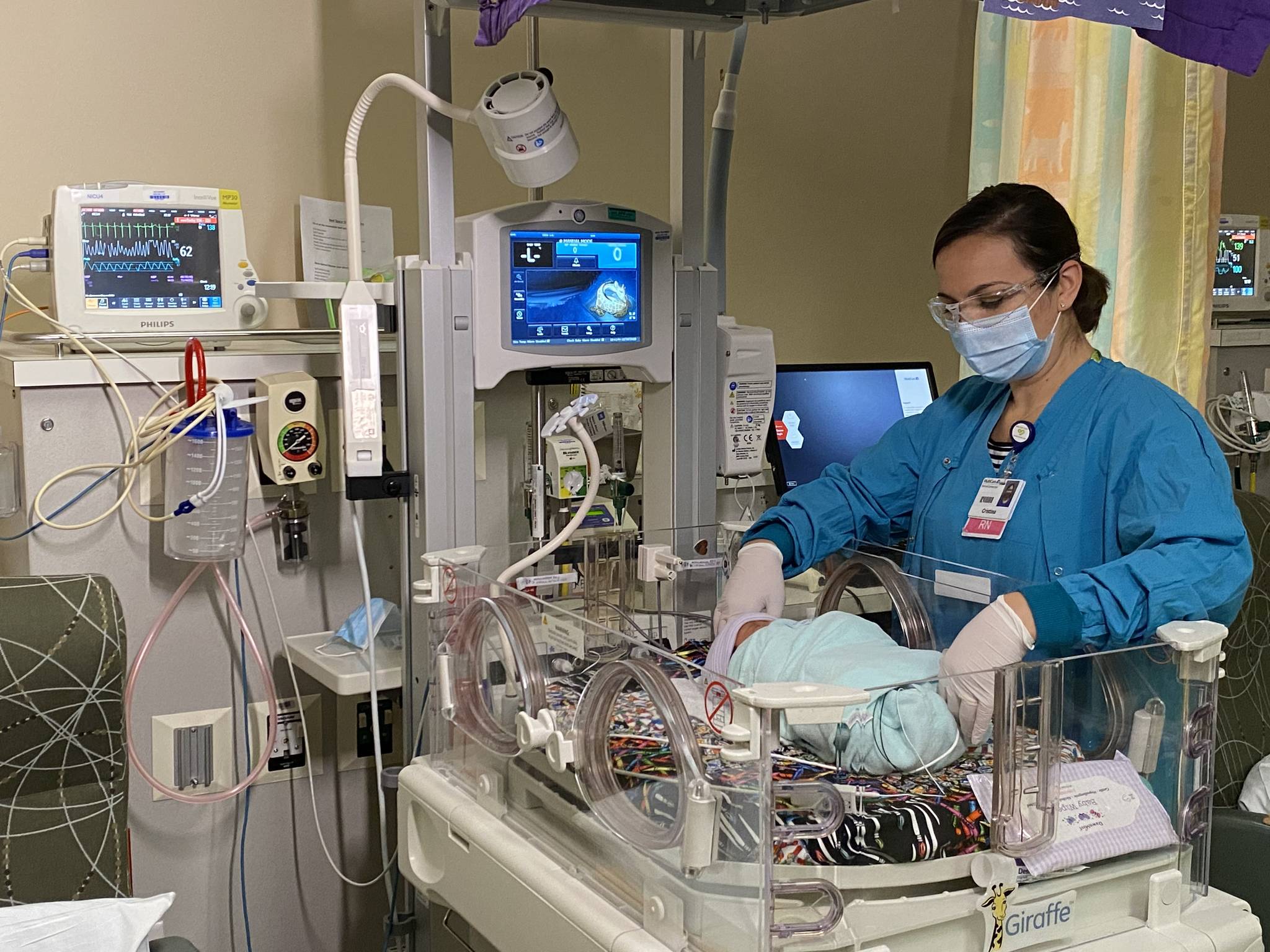

The hospital is licensed for 195 beds, but its physical capacity is 167, with 16 ICU beds, the rest being a smattering of what are called Progressive Care Unit beds, Medical Surgery beds, Observation Unit beds, Behavioral Health Unit beds and Neo-Natal Intensive Care Unit beds.”

The number of beds, Matthews added, grows and shrinks somewhat based on the hospital’s observation status cases. but it has a finite number of behavioral Health Unit beds, Geriatric, Psychiatric and Memory Wellness units that are cordoned off.

As a certificate of need State, Washington state says, “Yes, hospital or health care system, you can build a hospital, and you are licensed for a finite number of beds.” But the realities of construction and how those beds are divided into different subcategories can actually reduce the number to the hospital’s physical capacity.

MAMC’s COVID-19 numbers, Matthews said, represent less than 10 percent of the patients in in the hospital.

The hospital’s real challenge, Matthews said, has been to the cold, flu and respiratory ailment season, but at the same time managing the uptick in COVID-19 patients, which, he said, has made the hospital a much more busy place than it was only a few weeks ago.

Surprisingly, Matthews said, the number of those typical seasonal ailments are down a bit. The general belief, he said, is that the same public health behaviors that protect against the flu — distancing, masking, washing hands — happen to work well against COVID-19, too.

So, MAMC is handling it. But at what point will the alarm bells go off?

“I think our internal benchmark is that, essentially, we look at how full our Intensive Care Unit is, and our ICU has been approaching capacity, but every day we’re able to downgrade, so patients get a little bit better as they get out of the intensive care unit. So there’s still enough of a buffer that we feel fairly comfortable that we are able to manage the need of our very sickest patients,” Matthews said.

When the ICU fills with a large number of long-stay patients, that’s when, he said, the hospital would start to say ‘we need to be thinking as a region,’ and we already have plans in place to figure out how to transfer patients between our facilities and our ICU beds. We have a Mission Coordination Command Center that helps us manage those conversations, and that was set up a couple of months ago. It’s nice to know that it’s there and that it’s in the background helping us manage this, but we have not reached that point yet where we’d feel like we need to put together an instant command center and really manage each and every single admission in that regard.”

Could that happen if the number of positive cases continues at the current rate?

Definitely within the realm of possibility, Matthews said, which why the hospital is taking the issue so seriously.

“The thing that’s different between now and, say, March, was our availability of supplies and resources and PPE. We feel very comfortable in our ability to keep our staff safe through the presence of PPE. However, the thing to remember is that as and when the number of cases increases, there is a finite number of beds, and so that is now going to be the thing that we look at closely every day.”

Like other hospitals, MAMC has a rigorous system of staff protocols for symptoms based upon CDC-approved criteria. In addition to that, it offers testing for staff who become symptomatic, and rigorous guidelines as to whether those individuals must go home and quartine there. Indeed, the hospital has transitioned a large part of its work force to a work-from-home status.

“These are a couple of layers of safety that we are trying to build there. And then the PPE availability piece is very important. The thing with our staff that we continue to learn from this is that the vast majority of folks that actually develop symptoms convalesce at home for a number of days and are able to return to work. The key here is capturing the fact that an individual is becoming symptomatic, getting them tested appropriately, and then allowing them to quarantine, so that we are not exposing other members of the staff.”

Matthews said he is grateful to all of the unsung heroes on staff.

“When I attend staff meetings and department meetings, the thing that I continue to be amazed by is stories of resilience and gratitude, and yes, people are tired but they keep coming to work, and if they can get one patient who is struggling to breathe because of COVID-19 to really deescalate to the point where they are able to go home again, that feels like a huge win. It is those stories that keep our staff motivated and moving forward.”

Matthews emphasized how far treatment has come along since last spring.

“That’s one of the most exciting and reassuring things about this, that not only are we learning more about how to prevent individuals from getting it in the first place with. that whole public health approach of masking, handwashing, universal distancing, but when people get sick, at each level of sickness we are learning about the things that work. For instance, proning patients, that is putting them on their stomachs seems to help with something called alveolar recruitment, essentially their ability to exchange oxygen in their lungs better.

The hospital has medications, he said, which, thanks to Multicare’s participation in clinical trials, have been highly effective in reducing the length of acute severe illness and actually getting people better.

“But the message here is that it’s better not to get it at all, and our main job is to get through this long dark tunnel until we can get to the light of day with vaccines,” Matthews said.

He had the following advice for the community.

“I think I would be missing a good opportunity if I didn’t encourage people to be very thoughtful about their holiday planning and to make good decisions. People need to understand that this holiday season and winter season is going to be different. We are living in a different time, and if we can just be thoughtful, and perhaps just limit our gatherings for just this one year, we won’t have to deal with tragedy at the end of the year and into next year.

“That will really help that surge of patients we anticipate and maybe flatten the curve, so that we don’t have to get to the place we call ‘crisis of care’ where all of our facilities are operating at capacity,” Matthews said.