Ordinary asphalt and concrete mixes don’t allow water to penetrate, so it flows to the road side and passes into the ground with whatever pollutants it carries.

It’s an age-old concern sharpened to a point by the new emphasis on green technologies. Now four civil engineering students from Washington State University have come to Auburn to do something about it.

For their senior project, Brent Kunz, Ian Ambler, Rob Borden and Rebecca Matlack, will experiment with pervious paving concrete that lets water seep through and scrubs it clean before it touches the earth. They already have a bangup outdoor laboratory waiting for them called the Auburn Environmental Part. To test the idea, the students will rip up small bits of park-fringed Western Avenue and Clay Street Northwest, rebuild those sections with pervious concrete and see what happens when the rain falls.

Their arrival launches what Auburn City Councilman Rich Wagner, a retired Weyerhaeuser engineer, said will be years of collaborative efforts with WSU’s College of Civil Engineering using the sprawling park.

Wagner recognized this spring that the wetlands would make the perfect outdoor laboratory, a place to test new ideas, a magnet for engineering and science students engaged in urban storm water research. He pitched the idea to his friends Mike Woolcot, director of WSU’s Institute for Sustainable Design (ISD), and David McClean, Chairman of WSU’s Civil Engineering and Environmental Department, and they bit.

Wagner drew up the preliminary design for the first project — a pervious concrete slab with a sand layer underneath to filter the water and a base below to direct the flow to a french drain and possibly to a retention pond.

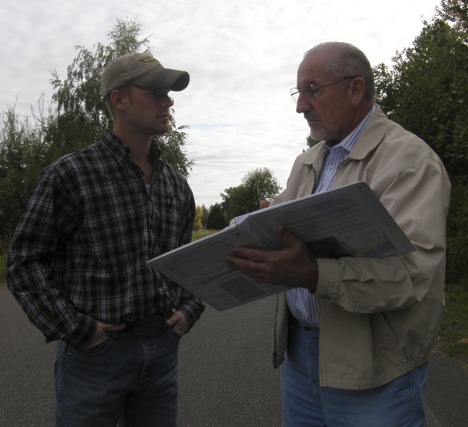

“We decided that we wanted to do the sections that are along the wetlands,” Wagner said, gesturing to Clay Street Northwest where he and Kunz stood on a recent day and east to Western Avenue. “That’s really what we are trying to prove here — new technology, new paving systems that would be friendly to the wetlands.”

Because pervious concrete has more voids in it than traditional concrete, Kunz explained, water can penetrate it. Stronger than asphalt, it doesn’t require as many supporting layers. That can save construction costs.

“This design was something Rich came up with, and we are using computer programs to reproduce this so we’ll have our own version of it, and we’ll be making changes to what you see here,” said Kunz. “We’re going to work with a design similiar to this on Western and Clay, although Clay Street will probably be wider than Western. The driving lanes on Clay will be about 12 feet apiece, but maybe only 10 foot lanes on Western.”

“What I’m trying to keep them focused on is that this is about three things: storm water retention; transport, so you move the water sideways, endways, whatever way you want the water to go; and treatment, because every one of those layers has some ability to remove pollutants. I gave them this as a starting point, but they will make some innovative changes to that as they move along,” Wagner said.

For engineers, that’s big stuff.

“…What’s not been proven yet is whether [pervious concrete] can be put on high-speed streets, but that’s part of what the engineers and scientists are working on, taking it from these kinds of arterial streets up to regular freeways,” said Wagner.

Solutions developed here can become national examples, and engineering-wise they will help businesses meet tough new regulations all over the United States, Wagner said.

On a recent visit to the wetlands, Woolcot explained why the Auburn-WSU partnership makes such great sense.

“It’s difficult to study and do sustainability while you are sitting in a university,” Woolcot said. “One of the reasons why this is a landmark deal is our integral involvement in the community in an explicit way. These are not wetlands tucked off to the side of the city’s development area, these are smack in the middle of Auburn. That is unique in the state.”

“There’s some really neat, real-world pieces that are incorporated into this particular project in terms of the water management issues, and we think we have some expertise that is going to contribute toward tackling some of the problems,” McLean said.

Wagner said the pervious concrete would be perfect for the proposed Promenade on South Division Street.

“It would solve a lot of our storm management problems down there. It’s a slow-speed street and doesn’t have a lot of trucks on it. That’s one of the reasons I asked for this senior project was to get something real for the City Council to look at, and then as we begin to move forward with the Promenade next year, we will consider it for that project.”

Auburn City Councilwoman Sue Singer got things rolling in the spring when she dusted off an old idea to bring green-related development and jobs to the green zone around the 86-acre Auburn Environmental Park. Then she moved beyond that idea by proposing to link several clean-tech incubators in the Puget Sound region and finally connecting private sector green collar businesses to a research university to help grow jobs.