Jim Warrick’s childhood in the Appalachian mountains of North Carolina has stamped itself indelibly in his honey-tongued, southern drawl, smooth as molasses.

But the teachings of the hell-fire-and-brimstone Southern Baptists who peopled the tiny town of Egypt and the county that surrounded it more than 60 years ago only confused him, fired up questions that defied answers, and finally led him to abandon the faith of his forebears. The answers to the many questions that threatened to burn a hole in his skull, the grown Warrick, by then a returned Vietnam veteran, a father and husband and a field engineer, would find only in the teachings of the Buddha.

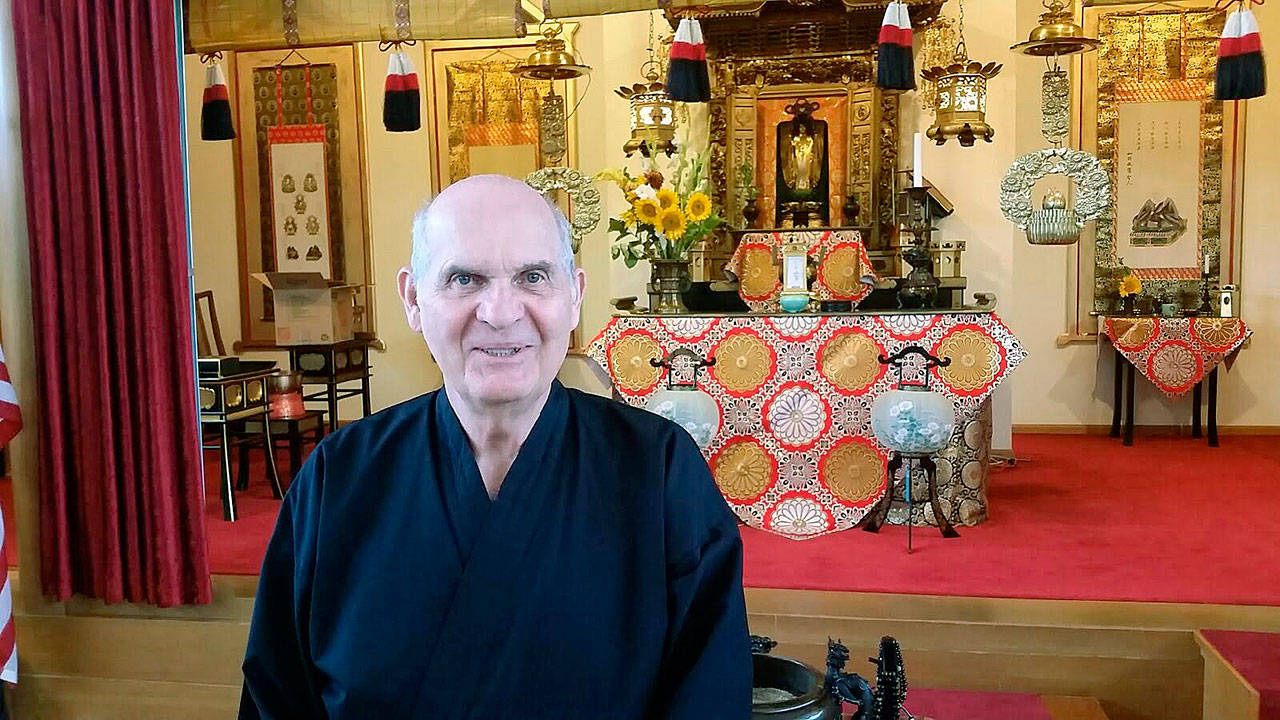

Today, Warrick is the freshly-minted reverend of the White River Buddhist Temple, the first Caucasian minister in its more than 100 years of existence.

“Baptist to Buddhist does seem a bit of a stretch, doesn’t it,” Warrick acknowledges with a smile.

He pulls out a Buddhist parable to explain himself.

Once, he began, there was a man who had been shot with a poison arrow and lay dying on the road. A good-Samaritan-type approached to pull out the arrow and relieve his suffering. But the bleeding man protested. Before he would allow the good man to remove the arrow, the sufferer said, he had to know who had shot him, man or woman, what kind of bow the archer had employed, what kind of arrow, and so on.

“The problem is not the answer to all those questions; the problem is the suffering that he is experiencing,” Warrick said. “The problem is how to remove the arrow and stop his suffering.”

Which is what the 4 Noble Truths of Buddhism teach: the reality and nature of suffering, and how to stop suffering.

Although Warrick, a veteran of the Vietnam War, was stationed in Japan and the Philippines during the conflict, he didn’t pick up his beliefs in the Far East.

“By the time I came back to the states, I had a wife and child, and I wanted to get back into the church. It just didn’t feel right. The Baptists teach things literally. God created the world in six days, and on the seventh day he rested. We’re asked to believe that God created Eve from one of Adam’s ribs. That didn’t work for me,” Warrick said.

Warrick looked into different faiths, including Judaism and Shintoism, but nothing resonated with him like Buddhism.

Warrick comes to Auburn after 30 years with the Seattle Buddhist Church, where he was ordained, and where he trained to become a Buddhist priest. He finished his internship at the Seattle Temple in 2010 but stayed on as an assistant minister until June 1 of this year, when temple elders assigned him to the Auburn temple.

Warrick will be among his new congregation at the White River Buddhist Temple at 4 p.m. Saturday, celebrating Bon Odori, or O-Bon, the most popular holiday in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. According to Jodo Shinsu tradition, O-Bon is called ‘Kangi-e’ or ‘a gathering of joy in gratitude.’ ”

Last year’s festival at the temple drew an estimated 1,000 people to welcome back the departed in spirit, and not only with dancing but also with drumming and feasting.

According to Buddhist teachings, Mokuren, a disciple of the Buddha, long ago beheld a vision of his dead mother indulging in her own selfishness in the realm of hungry ghosts. Troubled, he approached the Buddha and asked how he could release her.

Buddha answered: “Provide a big feast for the past seven generations of dead.” This the disciple did, gaining his mother’s release. It was only then that he started to see the true nature of her past unselfishness and all the sacrifices that she had made for him, and he danced with joy. From this dance of joy comes Bon Odori, or “Bon Dance.”

Bon Odori has existed in Japan for more than 500 years, bearing similarities to the Mexican observance of el Dia de los Muertos, with customs involving family reunions and care of ancestors’ grave sites.

“I love O-Bon, because O-Bon reflects our lives,” Warrick said. “In our lives, we’re not always happy, and we’re not always sad. There are two parts to the celebration. The first part is what we call Hatsubon, which mostly translates to ‘First O-Bon.’ It’s for the family members who lost loved ones from this time to this time last year. Last week, we had our Hatsubon service, so we reflected on their lives, and the sadness of losing those loved ones. The pain of loss is still very real even after a full year. It’s diminished somewhat, but it’s still very painful for those who have lost someone in the past year.

“This second part of O-Bon is not only for the families, it’s for everyone. It is our celebration of joy. It is a celebration of all those conditions that came about from all of our loved ones, from all of the people who have affected our lives, from the beginning. We can look backwards as far as we want to realize the profound affect people have had on our lives. It is for everybody, whoever you are, wherever you may come from,” Warrick said.