In King County, people seeking a protection order – a legal restriction to contact from a harassing or abusing individual – face complex processes, insufficient help and racial disparities in outcomes, according to a new report from the King County Auditor’s Office.

The findings of the audit were presented to the King County Council’s Law, Justice, Health and Human Services Committee on May 3.

The audit, which looked at protection order petitions in King County Superior Court between January 2016 and June 2021, found that while many petitioners received temporary orders, fewer received full protection orders.

Of the 5,512 petitions filed in Superior Court in the 18 months between January 2020 and June 2021, 78 percent resulted in a temporary order and 35 percent of petitioners obtained a full protection order.

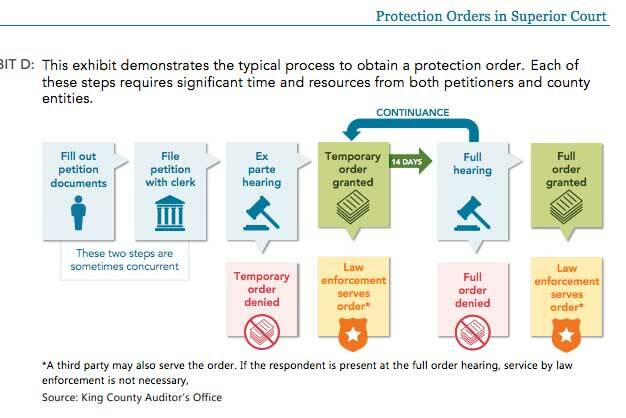

The goal is for protection order proceedings to be accessible to self-represented petitioners, but the process set by the state can be complicated and time consuming, according to the audit. The process is a multi-step legal process, with multiple forms and a minimum of two court hearings.

According to findings in the audit, petitioners are more successful in obtaining a full order when they have an attorney or advocate, but most individuals do not have this help. Between 2016 and mid-2021, only 9 percent of petitioners – across all types of orders – had an attorney.

Advocates in the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office who assist petitioners experiencing intimate partner domestic violence provided detailed filing assistance to only 11% of domestic violence protection order petitioners, and other assistance to about half of domestic violence petitioners, between January 2020 and mid-2021.

The auditors also identified racial disparities in protection order outcomes. From 2016 to mid-2021, Black and American Indian petitioners were less likely than other petitioners to obtain full protection orders. Only 33 percent of Black petitioners and 34 percent of American Indian petitioners obtained full orders, compared with 37 to 49 percent of petitioners of other races.

Even after new state requirements are implemented, auditors are concerned some barriers in King County could persist without additional improvements. Unless addressed, these types of barriers can make it difficult for individuals to navigate the process and may contribute to racial disparities in outcomes, including: limited resources to provide personalized assistance, gaps in language support for non-English speakers, inconsistent information on county websites, and lack of regular data analysis.

The auditors noted that King County Superior Court did not choose to fully participate in this audit, so they did not have the full and unrestricted access to all persons, property, and records that are granted to them by King County Code.

Instead, they based their conclusions on observations of public court proceedings, interviews with individuals in other agencies who play key roles in Superior Court’s protection order processes, and reviews of publicly available documents about Superior Court’s processes. With this approach, auditors were able to see protection order processes as a person going through the process might see them.

The county auditors recommended a number of measures and actions to improve access and remove barriers to these orders for those in need, including: a workgroup to work with stakeholders to improve the process, better data tracking for protection order outcomes, improved assistance for self-represented protection order petitioners, comprehensive state legislation on the issue, better informational resources for petitioners, and improved access and resources for non-English speaking petitioners.