By LaVendrick Smith

WNPA Olympia Bureau

The Department of Ecology is in the early phases of assessing its proposal for a cap on greenhouse gas emissions, and opponents already are questioning whether Gov. Jay Inslee and the agency have the authority to act on emissions and whether the rule’s impact on businesses is getting proper attention.

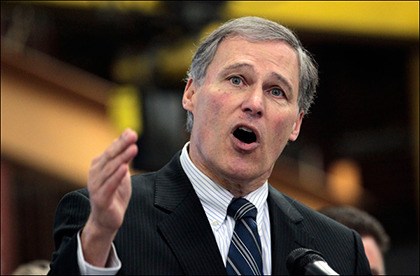

Inslee instructed the department to draft a rule in July after failing to gain carbon-emissions legislation last year. If implemented, the proposed Clean Air Rule would force the largest producers of greenhouse gasses to reduce emissions by 5 percent every three years starting in 2020, continuing to 2035.

“This is not the comprehensive approach we could have had with legislative action,” Inslee said during the announcement of his directive to the Department of Ecology on July 28.

“But Senate Republicans and the oil industry have made it clear that they will not accede to any meaningful action on carbon pollution so I will use my authority under the state Clean Air Act to take these meaningful first steps,” he said.

However, a bill this session sponsored by Sen. Doug Ericksen, R-Ferndale, chairman of the Senate Energy, Environment and Telecommunications Committee, attempts to block creation of the rule. Senate Bill 6173 would prohibit the Department of Ecology from passing any rule or policy limiting greenhouse-gas emissions.

The Ecology department’s proposal would require emission reductions by companies such as natural-gas distributors, waste facilities and power plants that emit 100,000 metric tons or more of greenhouse gases. The 100,000 metric ton threshold, beginning in 2020, would decrease by 5,000 every three years until it reaches 70,000 metric tons in 2035.

“We’re considering this a draft rule,” said Camille St. Onge, spokesperson for the department.

In a hearing on the bill Tuesday, Ericksen expressed concern that the Clean Air Rule would raise business costs for companies in the state, and even force some to leave the state.

“At the current time, we have the state in flux,” he said. “I can’t imagine being the CEO of a corporation that wants to create manufacturing jobs, looking at Washington state, and saying ‘how do I come into that environment and try to make the capital investment?'”

Other critics are also up in arms over the proposed rule’s impact on business.

“It’s definitely not built to serve multiple different types of users as it stands,” said Mary Tyrie, communications manager with Avista, one of the companies that would have to comply with the rule. Avista, a Spokane natural gas distributor, is the first business named on the department’s list of companies required to comply if the rule is adopted.

Tyrie said the Clean Air Rule presents unique challenges for the company because it supplies gas that is used by customers for electricity, and their emissions occur indirectly.

“We are not creating the emissions ourselves,” she said. “We supply the fuel that the customer burns.”

She said the company would have to take advantage of the proposal’s provision to purchase carbon credits from other companies able to reduce emissions, and doing so would cost money – and raise costs for customers who use their gas.

“Unlike the governor’s legislative proposal to the 2015 Legislature, this regulatory cap would not charge emitters for carbon pollution and therefore would not raise revenue for state operations. The other key difference is the current proposal wouldn’t create a centralized market for trading of emissions credits, though emitters may be able trade amongst themselves,” a statement from the governor’s office noted.

A tax on energy?

Brandon Housekeeper, government affairs director for environmental policy for the Association of Washington Business, called the rule a tax on energy. He said Washington and the state’s businesses are already a leader in efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Housekeeper said businesses are worried that the proposal is a “one-size-fits-all” approach that doesn’t take account for companies’ existing environmental practices. “We think given that Washington is already a leader in reducing emissions and using clean green energy, that there are better approaches we can take,” he said.

Additionally, Housekeeper and other critics have raised concerns over the governor’s ability to authorize such a proposal. They believe he doesn’t have the power to act independently of the Legislature on the issue.

Ericksen’s bill is also an attempt to gain some legislative oversight of carbon emission proposals. He said the Legislature can’t control carbon initiatives that are on the ballot in upcoming elections, but wants to see the department’s proposal go through the legislative process.

“What we can control is whether or not the executive branch goes forward with a carbon-cap rule,” he said.

Carbon Washington’s Initiative 732 would impose a $25 tax on every metric ton of carbon from fossil fuels used in the state. Another group, the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy, is preparing its own initiative that would direct investments toward helping the state transition to clean energy, and help reduce impacts on climate change.

Ericksen’s bill, co-sponsored by Sen. Tim Sheldon, D-Potlatch, vice-chairman of Ericksen’s committee and a member of the Senate’s republican caucus, would likely face an uphill battle in the democrat-controlled House, and if it were to make it to Inslee’s desk, the governor could exercise his veto authority.

Inslee and the Department of Ecology maintain they have the right to create the rule and enforce a policy through the state’s Clean Air Act.

“We are charged under the Clean Air Act to regulate air pollutants in Washington state, and carbon pollution is an air pollutant,” St. Onge said. “Greenhouse gasses are a known pollutant, so that falls under our purview.”

Ross Macfarlane, with the nonprofit Climate Solutions, says criticisms of the proposal are unsubstantiated, adding that the government acting on greenhouse-gas regulation is good for business because some businesses are worried about the impact climate change will have on their companies.

He called the move toward clean energy a critical revolution for the 21st Century.

“The question for Washington is: Do we want to be leading in that revolution,” he said. “Do we want to be a Silicon Valley or do we want to be a Detroit or rustbelt community that is left behind? And I think the answer to that is clear.”

St. Onge said the department expects to adopt a final rule in the summer. Meanwhile, the department is accepting comments from the public about the proposal, and plans to hold four public hearings in March. The department also plans to create an advisory committee to help form the proposal.