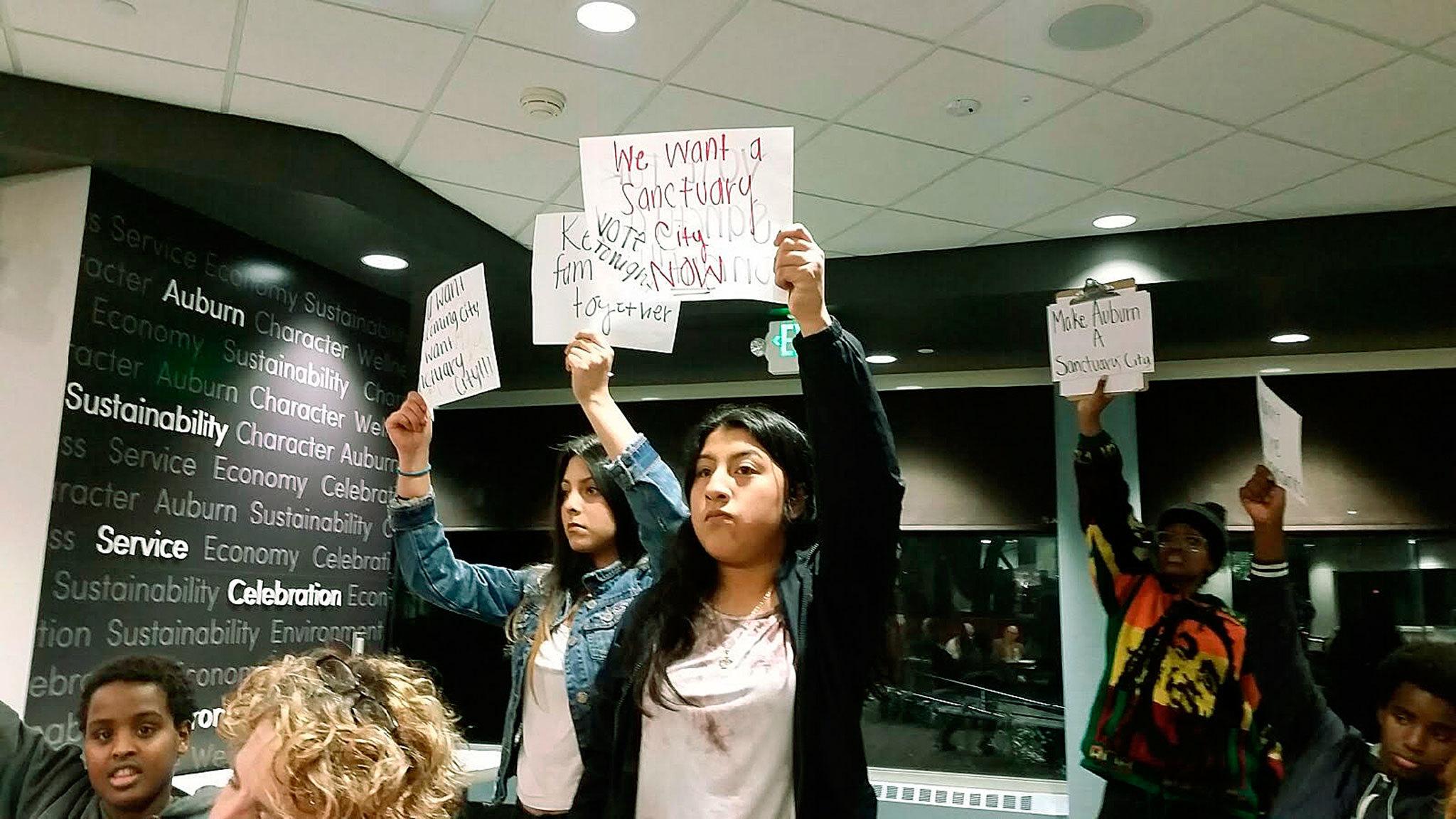

One afternoon two weeks ago, about 75 students marched out of Auburn High School and continued west along Main Street to the steps of City Hall to sound a pointed demand over the plaza.

“We want a sanctuary city, now,” they cried.

A demand for Auburn to declare itself the sort of city that does not prosecute undocumented immigrants for violating federal immigration laws in the country in which they are now living.

Between then and last Monday’s City Council discussion of the issue, the Trump administration declared it would withhold federal funding from jurisdictions that declare themselves “sanctuary” cities.

If that threat from the top did not faze activists, it did spook the City of Auburn, which could lose millions of federal dollars every year that pay for streets and a number of city services.

What activists found at Monday’s discussion was no enthusiasm on the council for adopting the hot-button phrase. Instead, they heard lots of talk about emphasizing Auburn as an “inclusive city,” a phrase that has been on city signs for almost nine years.

Whether that wording is formalized in an administrative policy or not, said Councilman Rich Wagner, “We ought to be featuring it so that citizens know about it. … I think most of the things that people would like to see (related to) discrimination and safety are in this inclusive ordinance. The one thing we already do – but should highlight – is that we have administrative procedures for the police about what we expect for them to do their jobs,” Wagner said.

He added that the public needs to know the City is mandated to cooperate with the federal government, but it’s not Auburn’s job to enforce federal immigration laws.

“This has been in place for almost nine years now, that we are an inclusive city,” said Councilman John Holman. “Perhaps it’s time to modernize the language in it. …We’ve had it for nine years, we should make it our own, and upgrade and modernize the language to make some human rights statements about our willingness to respect one another in Auburn.”

Police procedures

Turns out the demand for sanctuary city status may be moot. As Police Chief Bob Lee told council members Jan. 23, none of his officers ask about anyone’s immigration status, designation or not.

Assistant Chief William Pierson fleshed out the chief’s explanation Monday.

When an officer pulls over a car for a traffic violation, Pierson began, that officer asks for three things: a driver’s license; registration; and proof of insurance.

Should the driver not have a license on him or her at the time, Pierson said, the officer then checks the person’s name and date of birth with the state Department of Licensing and ultimately the nation-wide system.

“Why are we doing that? Because when you are driving, you have to have a license with you. It’s an infraction, if you don’t,” Pierson said. “If you don’t have ID with you, and we check with the DOL and no record is found, now you are actually getting to the misdemeanor realm, which is driving without a license on your person and no valid ID. Now it’s up to the discretion of the officer whether to arrest that person and take them to our facility to be fingerprinted so we can determine who they are.”

Police do this, Pierson continued, so the officer can determine whether he or she is issuing a ticket to the right person.

“Second thing – and it’s very common – people tend to lie to the police,” Pierson said. “I don’t why, but they do. And we become very suspicious when we can’t identify somebody through the system. And we treat every driver and every motorist that way, whether you are green, blue or yellow.”

Pierson noted that the federal government, which constantly monitors the local database, may check one’s immigration status when that person is at the SCORE Jail, and at that point may choose to come down and enforce its rules.

“We don’t enforce that piece with them. We’re just following state law. Everybody would be treated that same way,” Pierson said, adding that the procedure remains mostly the same for domestic violence and other crimes.

Activists listened and stayed silent as the conversation went on. But when they found out that they would not be able to address the council – which is not allowed at study sessions – they were furious. The first attempt to speak drew an unusually sharp rebuke from Deputy Mayor Largo Wales.

As activist Bryan Rivera complained, he and his friends had come to City Hall that night because somebody on the council had told them they would be able to talk.

“We were invited to be part of this meeting, personally,” Rivera began before Wales cut him off.

“No, you were not,” Wales snapped. “You were personally invited to be part of the audience, and if you had come on time, you would have heard that this was a study session for us to have internal dialogue on the policy and to establish inter-direction.”

Wales invited Rivera and his friends to attend the next council meeting, where they may speak.

The meeting is at 7 p.m. Monday, Feb. 6.

Expect a crowd.