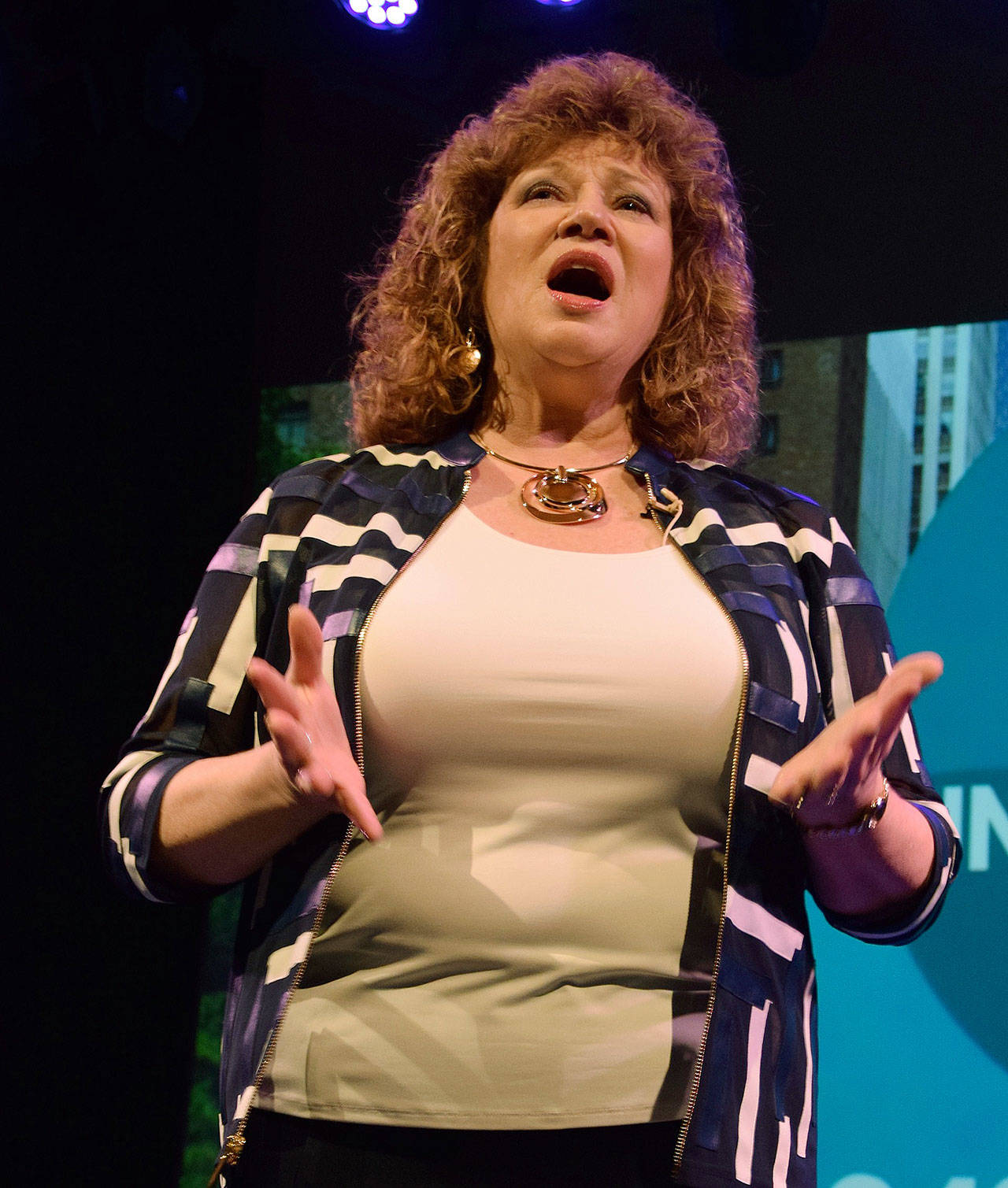

Mayor Nancy Backus wants the City and its residents to work together in a common cause fostered by their collective love of community, as she told the crowd at Auburn Avenue Theater on Tuesday night to hear her annual State of the City address.

But, Backus noted, of the 28,000 people interviewed in 26 cities throughout the United States for a study conducted by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation between 2006 and 2009, a mere 24 percent was attached to its community, 36 percent was neutral and 40 percent was unattached to its community.

“The question I present to you here tonight is, how can we, as your city government, foster and grow our collective love of community? … Many times, city government is seen as the functional end of a community. We ensure that the water flows into our homes, that roads and buildings are safe for use, that the streetlights come on at night,” Backus said.

But if that is all the City strives for, Backus said, it is missing its larger purpose.

“When we treat our role as a city in a mechanical way,” Backus said, “we create a result that is lifeless. But when we lead from a place of true love for our community, the result is a rich driver of economic and social development … I want better for Auburn, and I believe that by finding ways to strengthen our attachment and commitment to our city, we will create a city that enriches all of us.”

For the City of Auburn, it all starts by providing and maintaining basic infrastructure.

In 2017, Backus said, the City invested more than $30 million in capital projects, not only to reduce congestion and improve the safety of local roadways for pedestrians, cyclists and motorists but also to enhance health and safety by alleviating flood risks of the Green and White rivers and improving water capacity and security.

To break that down a bit, the City replaced more than 30 miles of deteriorating roadway, added and repaired more than four miles of sidewalk, installed six new traffic signal systems, two dynamic message signs and three rapid-flashing beacons at non‐signalized crosswalks.

Those improvements, Backus said, have increased the movement of traffic through the city by letting vehicle-censoring trigger precise automation that maximizes traffic flow and alerts drivers to traffic problems ahead. The improvements have likewise increased the safety of bikers and pedestrians, Backus said, in particular of Auburn’s children, many of whose feet pound these well‐traveled corridors on their way to school.

The City added more than a mile of water main, a mile of sewer pipe, two miles of storm drain pipe, three new water-pressure- reducing valve stations, two new system well pumps and tested the water supply for safety more than 1,500 times. In total, Backus said, the City’s maintenance and operations team completed nearly 22,000 resident‐submitted tasks.

All of that in a city that in the last five years has grown from 70,000 to nearly 80,000 people.

“We are no longer the small suburb in the shadow of the big city. We have grown into our own. But as we have seen our region thrive and expand at an unprecedented rate, we have also been faced with the larger challenges of this growth,”Backus said.

Growing pains

One out-sized challenge is affordable housing.

As demands on Seattle housing increase rent and drive down availability, Backus said, the ripple effects are stressing not only Auburn but the entire Puget Sound region. And when people who can’t afford to live in the urban core any longer move farther into South King County, the stock of housing tightens, too. And as demand grows, so do prices, and the challenge for everyone then is how to ensure this transition does not drive those already at risk for homelessness completely from their homes.

“We are seeing this trend on the national level, but nowhere has it been more intensely concentrated than here in the Pacific Northwest,” Backus said.

In 2017, she said, a count of the unsheltered in the region found 1,102 such individuals centered in the Renton, Burien, Kent and Auburn sub‐region. That is nearly 20 percent of all homeless individuals in King County. Seventy‐three percent of those individuals identified housing costs as their primary barrier to moving out of homelessness.

Backus said the City of Auburn has not stood idly by while the crisis continues to spread.

In January of this year, Backus said,, she joined King County Executive Dow Constantine and Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan to co-convene One Table – a regional initiative that looks to address homelessness by tackling its root causes, including housing affordability.

In August of 2017, the City of Auburn, in partnership with Valley Cities and the Auburn Food Bank, opened on I Street Northeast the Ray of Hope day shelter, focused on breaking the barriers that keep many in the cycle of homelessness. At one location, the center provides access to services like job training and support, hygiene services, and mental health and substance abuse treatment.

“I do not believe in giving hand‐outs, but I believe whole‐heartedly in providing a hand‐up to those who are looking for a way to move forward. Many times that can be something as simple as having the ability to register for a driver’s license, a key requirement when applying for a job. … Or it can be something as small as having a fresh shave and haircut for a job interview,” Backus said.

Addressing this challenge goes far beyond treating the outcome of homelessness, Backus continued. It starts with stemming the tide from the outset by protecting the security of housing for those already at risk in the community.

In 2017, Backus said, the City of Auburn provided more than $390,000 to residents for critical home repairs through its Housing Repair Assistance program. This program provides low‐income homeowners with grants for emergency home repairs – everything from repairing a leaky roof to fixing a broken furnace.

Tackling a crisis

Acting in isolation or with indifference will likewise fail to resolve the drug epidemic, Backus said.

Last June, the City held a town hall at the Auburn Avenue Theater to address the startling rise in drug addiction that is sweeping the nation. It asked experts from throughout Auburn and the region to speak about what has driven the epidemic of opioid drug use and what can be done to combat it, Backus said.

“Embracing those brave enough to tell their stories, removing the stigma surrounding addiction, and listening with open minds about real solutions is the only thing that will move us out of this crisis. We must begin to see this issue for what it truly is if we can ever begin to change it,” Backus said.

In 2016, Backus, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray and Renton Mayor Denis Law co‐convened the Heroin and Prescription Opioid Addiction Task Force composed of 43 agencies – including the Auburn Police Department and the Muckleshoot Tribe ‐ to develop a comprehensive strategy that focuses on prevention and on increasing access to treatment on‐demand and reducing fatal overdoses. This task force returned last year with a list of eight key recommendations falling under the categories of primary prevention, treatment expansion and enhancement, and health and harm reduction, Backus said.

“One of the most controversial of these proposed solutions was safe injection sites. To be clear, Auburn voted against this recommendation, and has since taken further action to ban such sites from our city. But there were findings from this task force that we whole‐heartedly support and have already begun to implement here in Auburn, including the distribution of Narcan,” Backus said.

This year, every patrol unit within Auburn’s police department was outfitted with this life‐saving overdose reversal drug. In less than 12 months, officers had administered it 25 times – three times resulting in life-saving medals of honor for those officers.

During this past year, Backus said, the Auburn Police Department has doubled the number of bike officers on patrol, part of 10 new positions created within the last 12 months. Last year alone, she said, Auburn saw a 17.9 percent reduction in overall crime.

From the ashes

The evening’s most impressive moment came when Backus recounted the Heritage Building fire and its aftermath.

“In the week that followed the fire, our city showed an outpouring of love that is truly unprecedented,” Backus said, as images of the fire and varied tableaus of the community’s big-hearted response flashed by on the screen behind her.

After the fire, donations of clothing, food, household goods and furniture to outfit the displaced families filled gymnasiums and storage buildings to capacity.

After the fire, restaurant owners jumped into action overnight, organizing hot meal deliveries for people staying at the Red Cross Shelter.

“Within three weeks, our economic development, emergency management and human services teams had secured a disaster designation from the governor – opening up funding and assistance for these residents and small businesses.

“Today, just over eight weeks later, five of those nine businesses have either identified new store locations or are fully open and operational – most right back here on Main Street,” Backus said.