King County Metro, which previously touted its goal of adding 20 express bus lanes throughout the county by 2040, has now lowered that benchmark to seven by 2027.

At the beginning of 2017, the King County Council approved Metro’s official – and ambitious – road map for its regional transportation network Metro Connects. Part of the plan called for greatly expanding the RapidRide system, a type of bus line intended to provide frequent and speedy service on high-demand routes via designated lanes and allowing riders to enter buses from multiple doors. The lines are construction intensive because they require new stations, off-vehicle payment infrastructure and bus lanes.

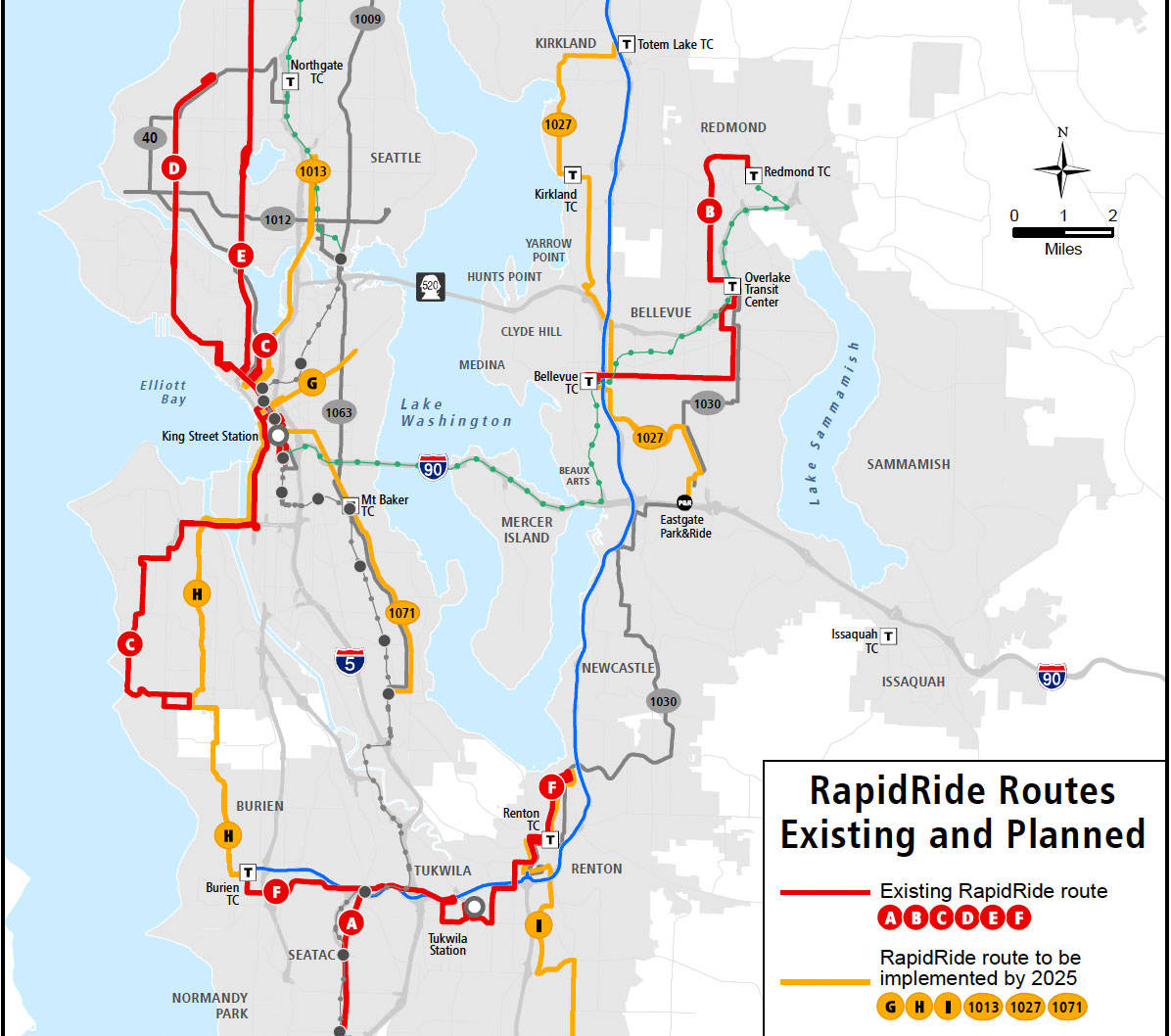

Since 2010, the transit agency has already built six RapidRide lines, such as the A Line that runs between the Federal Way Transit Center and the Tukwila International Boulevard Link Station. Metro Connects called for adding 13 more lines by 2025 and another seven by 2040, for a total of 20 additional lines. Metro boasts that the planned RapidRide investments under its vision would bring “frequent transit service to 70 percent of King County residents.”

Despite the previously ambitious goal, however, Metro has since quietly scaled back its construction timelines. The agency now states that it can only deliver six lines by 2025 and an additional seventh by 2027. The other 13 have no clear timeline for completion.

One of the six lines to be delivered is the I Line, which would connect Auburn, Kent and Renton, and is expected to come online in 2023.

“The 13 lines by 2040 is going to be determined,” Jeff Switzer, a Metro spokesperson, told Seattle Weekly.

According to Hannah McIntosh, Metro’s program manager for RapidRide, a number of factors are responsible for the shift, including increased regional construction costs, the high demand for qualified consultants and engineers in the area, and ongoing uncertainty about the flow of funding for local transportation projects from the Federal Transit Administration — an agency overseen by the Trump administration. His administration has threatened to withhold grants from jurisdictions like Seattle in recent months.

“We took all of those factors into account and worked hard to build a responsible and realistic deliverable timeline for RapidRide implementation,” McIntosh said. “It’s a difficult time to be putting design and construction contracts out on the street.”

McIntosh added that some federal funding has been trickling in for local projects, but not as quickly or regularly as it was during the prior president’s tenure. “It’s not that we don’t think federal funding will be there, it’s that we’re building in more time to pursue federal funding.”

McIntosh stressed that the timelines identified in Metro Connects were never set-in-stone deadlines to which the agency had to adhere.

“It was an identification of need countywide,” McIntosh said. “And the next steps of coming out of that visioning process are laying out what we can do to make this vision a reality. There is no lessening to [our] commitment to the full vision. We as an agency are still 100 percent behind that vision, but we want to implement it in a sustainable way.”

Among the 13 lines now on hold are one running between Seattle’s Ballard and Wallingford neighborhoods, and another connecting the Rainier Beach neighborhood to SeaTac and Federal Way.

King Couty Executive Dow Constantine’s proposed 2019-2020 budget has identified county funding for the seven lines that have been given clear timetables. Five of the seven lines have secured some federal funding, and Metro will be seeking more grant money for three of those lines.

Two routes — the Bellevue to Totem Lake line and the South King County line — have not received any grants to date, but Switzer said Metro plans to apply for funds for those projects.