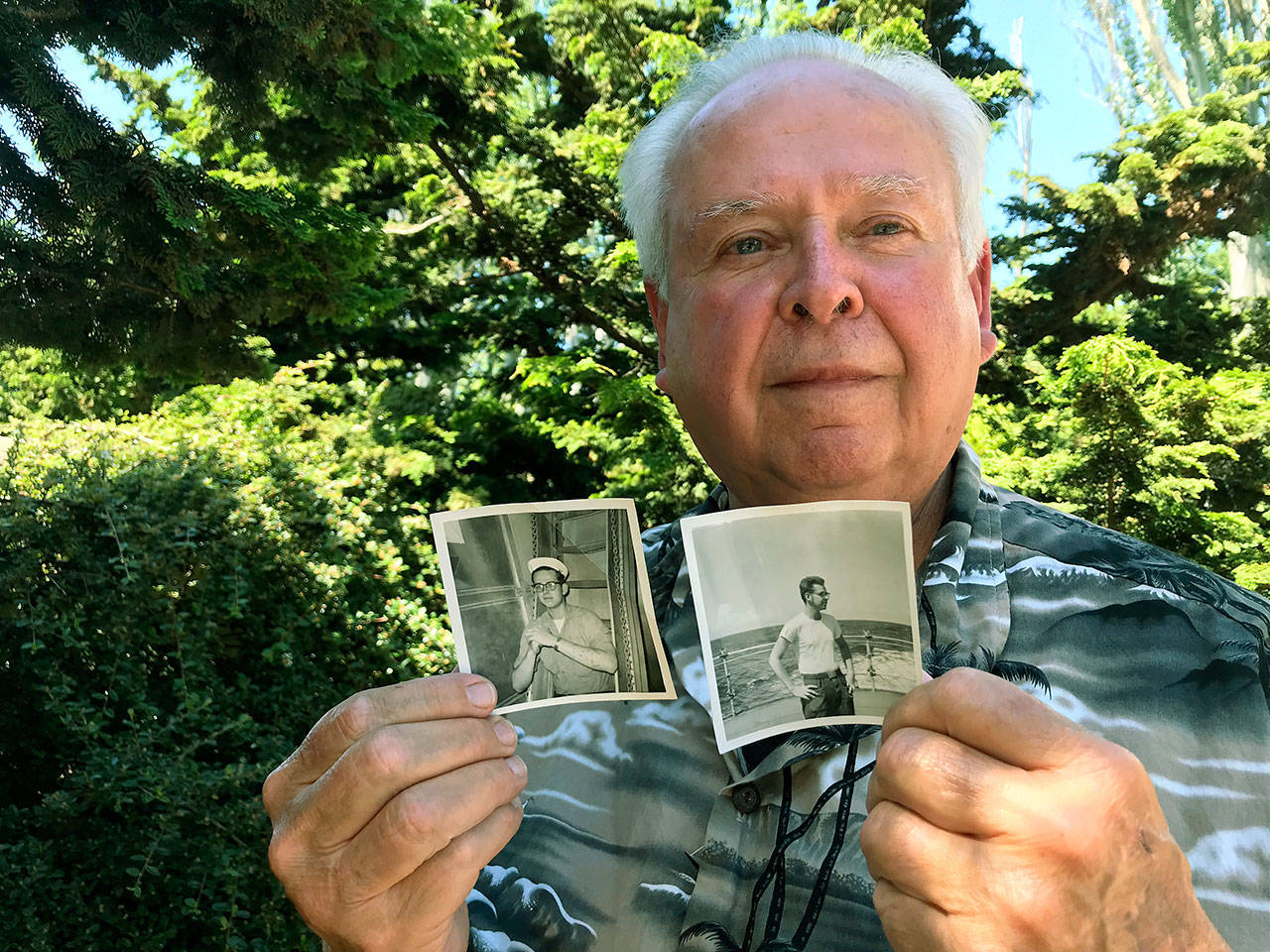

A restless, adventurous Pete Lewis joined the Navy at a time when the military was accepting just about anybody, and tensions were mounting in a faraway place called Vietnam.

The skinny kid with Coke bottle eyeglasses from Omaha, Neb., was fresh out of high school and eager for change when he asked his father, a Navy captain, for permission to join the service, learn a trade and find his own way.

“He was shocked,” Lewis recalled, “shocked that I joined.”

Little did Lewis know what he would encounter on a destroyer destined for troubled waters.

“No 17-year-old kid really knows,” Lewis said. “We were all a bunch of kids, and we were all indestructible.”

Like many young sailors and soldiers before him, Lewis left home as an innocent and energetic boy, only to return stateside a fractured, angry man. He was shunned, a veteran scorned for fighting an unpopular, confusing and ultimately lost war in Southeast Asia.

The Vietnam War experience during the turbulent ’60s left emotional wounds on the young man, but Lewis would overcome the dark times with the help of others. He would move on, return to college, marry, raise a family and spend a lifetime devoted to public service while helping fellow veterans prosper in a community he embraces. Lewis became a bank manager, a politician, a councilman and ultimately, a three-term mayor of Auburn (2002-14).

“I am mixed (emotionally),” Lewis said of his nearly four-year stint with the Navy. “I’d do it again. … it changed me. After my time (there), I knew I could stand on my own.”

Lewis didn’t know it at the time, but he and his shipmates were to be a part of history, adding a significant chapter to the Vietnam War story. Lewis, a 2nd class petty officer and radarman, was aboard the USS Higbee – a storied World War II and Korean War destroyer with 5-inch guns – that screened carriers in the South China Sea during the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in August 1964.

The incident, in which a U.S. destroyer allegedly clashed with North Vietnamese fast-attack craft, convinced President Lyndon Johnson to authorize an increased American military presence, deploying ground combat units for the first time and boosting troop levels. The war would escalate for years to come, with no end in sight.

Lewis suspected growing hostilities from what popped up on his crowded radar screen.

“I know there were (enemy) torpedo boats because I could see them,” he said. “There’s been some controversy on whether (the Tonkin confrontation) happened. … I know it happened.”

In the ensuing days and months, the USS Higbee patrolled the sea and coastline, providing naval gunfire support for U.S. forces off of South Vietnam. The warship played many roles in the Vietnam theater, Lewis said. It supported Marine brigades, bombarded enemy positions, intercepted submarines, shadowed Russian ships and helped rescue the Arsinoe’s crew after the French tanker grounded off Scarborough Shoals in the South China Sea.

The Higbee-escorted fleet lost four ships during Lewis’ time in the gulf. The ship survived enemy strafing and weathered two typhoons.

Lewis lost friends on those early battlefields. He lost a close friend, whom Lewis had encouraged to join the military. News of the Marine’s death was a painful blow to the then-turned 18-year-old Lewis.

“There were never any good times after that,” Lewis said. “I couldn’t recover from that.”

Tough times

Lewis divorced the Navy and refused to look back. He carried that rage and bitterness long after he was discharged from service. He worked at a beach hotel in Mexico, then returned to San Diego, where he went to college to study finance and political science.

During his toils as a student, Lewis survived two awful accidents – a fall from a steep campus step-way, and a car crash down a canyon. Lewis was driving along a winding road when the vehicle suddenly lost its power system, struck a guardrail and flipped. Lewis somehow ejected through a car door and wound up with a busted spine and injuries that required a long recovery.

“There was time in my life when things did not go well,” Lewis said.

His fortunes turned when he met his future wife, Kathy, who became his rock, his foundation for a good life.

Lewis gradually found peace and purpose. Through a series of events, he began to reconnect and give back to veterans.

When Lewis became Auburn’s mayor in 2002, he worked tirelessly on many veterans’ issues locally, regionally and nationally. Notably, he co-sponsored the Veterans and Human Services Levy that King County voters passed in 2005 to generate funding for veterans, military personnel and their families through a variety of housing and supportive services. That measure was renewed in 2011.

Lewis spoke out in support of veterans, making national news by urging mayors throughout the country to listen to vets and address their issues.

“While veterans have been termed a problem by many,” he said at a U.S. Conference of Mayors meeting in 2012, “we must recognize that they have earned the assistance we bring, while, at the same time, we must remember the value they bring back to us with their return home. Our veterans can be an agent of positive change for our community.”

As mayor, Lewis committed considerable time to many civic, community and veterans organizations, serving on various committees and directing projects. Lewis, a member of VFW Post 1741, continues that work today.

Recently, he was part of the leadership team that brought the joint American-Vietnamese War Memorial to Les Grove Park.

Lewis acknowledges the challenges of today’s veterans who have served and survived combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s important, he said, to recognize veterans and to help them transition to civilian life.

“You have to reach out to them,” Lewis said, “and not expect them to come to you for support.”

Lewis should know. Vietnam left a mark.

“None of us were really prepared for what happened,” he said of the cold home reception from the war. “We could not make any sense of it.

“You changed,” Lewis insisted. “You came back a different person.”

And a better man.