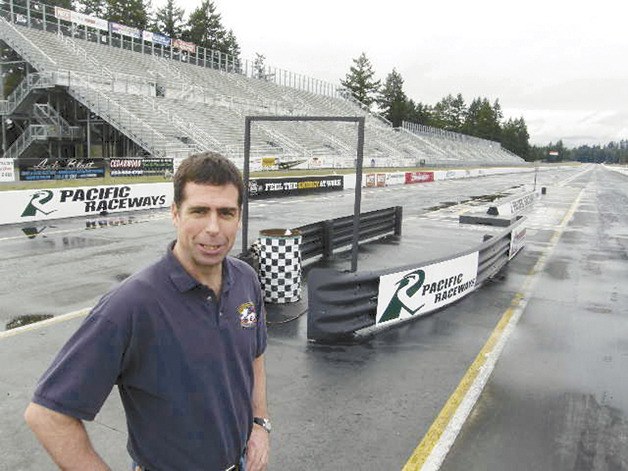

Jason Fiorito grew up working in the family’s construction business, so he knows a lot about building roads, driving bulldozers, backhoes and earth movers.

He never imagined when his family took over operations of Pacific Raceways in 2002, however, that he’d be locked in the battle he’s in now: trying to save the racetrack his grandfather, J. Dan Fiorito, graded and paved east of Auburn for a band of cash-poor investors 50 years ago in exchange for a share of stock.

And do it over the angry opposition of neighbors who want to kill his expansion plan. Too noisy, too detrimental on nearby Soos Creek and the water table, opponents say.

“I never thought I’d be fighting for my right to exist,” said Fiorito, 42.

Fiorito’s problem is that the operation of the current road course and drag strip don’t support the maintenance of the racing surface. They certainly don’t support the debt service payments he’s been making on the $5 million loan he took out to bring the venue to where it can operate at a club racing level on the road course and a professional level on the drag strip.

The loan helped arrest the slow, sad slouch into decline that took the track from the world-class facility it was when it opened on July 4, 1960 to the brink of ruin by 2002, Fiorito said. That, he said, was the result of a series of unfortunate leases the original investors entered into with lessees who did nothing to maintain the track for 30 years.

When the Fiorito family took over operations of the former Seattle International Raceway (SIR) after the last of those disastrous leases, it tore down the buildings, replaced the bathrooms and began an aggressive, deferred maintenance program to establish some safety-runout areas around the road course. It rebuilt the grandstands, replaced many of the wooden seats with aluminum seats, paved some pit areas and cleaned up the property.

But Jason quickly learned a vital lesson: road courses and drag strips don’t make that much money. He also realized that if Pacific Raceways was to remain competitive, he would have to make changes.

Fiorito looked for a sustainable business model outside of the impossible scenario of hosting a NASCAR event. He decided to do as other tracks in his situation had done and build an associated industrial park. By building and renting out industrial and commercial space for businesses tied to the racing industries, he could keep things going and make the venue a world-class facility once more. He said no buildings will be built on spec.

Economic boost

He said the industrial park could help create 1,000 jobs, and he estimates its economic impact on the local economy at about $30 million per year.

By surrounding the track with those buildings, he said we can cut the noise.

“As it sits now, it’s not really a sustainable model. In terms of our ability to survive, we have a limited lifespan as a club racing track with deteriorating facilities. And the only way to realize the economic impact, the social benefits and our ability to survive is to move forward with the proposed upgrades,” Fiorito said.

Fiorito said his master plan will work because it “efficiently uses every square foot of the property” by providing racing surfaces required by racing’s sanctioning bodies and activities he said the region deems necessary.

“Our plan is to replace a grass field with a regional-size oval,” Fiorito said. “This is the one additional racing surface that we propose in the master plan.”

Ovals have been disappearing over recent years with the closure of such tracks as Spanaway and Portland speedways. If the ovals are lost, he said, with them would go the stock car industry from Washington state, which would benefit nobody.

The rest of the property will be taken up by an existing shifter kart track, a permitted, relocated diagonal drag strip on which construction is already underway, an upgraded road course to meet professional sanctioning standards, an NHRA drag strip and a relocated motocross track.

“Our vision is to have five racing surfaces that can be operated on a regional level,” Fiorito said. “In the event we have a professionally-sanctioned road course or drag strip event, we can shut down the other four spectator-driven events and use their parking lots. We can have parking for 50,000 where we have 30,000 now.”

He said a traffic revision will allow that to happen without causing the present-day backups on Highway 18.

He said the second drag strip will allow for simultaneous running of club level drag racing only and road racing on the road course, thus ending activity at the track by 5:30 or 6 p.m. instead of carrying on until 11 p.m., which is the case now.

A lack of safety runout areas, he said, constrains the present road course.

“In 1960, there were few trees alongside the racing surface. Because of 30 years of lack of maintenance, however, there are trees growing up right alongside the track, so that if a car leaves the racing surface, it will hit a tree. The solution is to remove trees, and that means getting into sensitive areas and removing vegetation to provide flat runoff areas, so that if a car going 200 mph plus leaves the track, it won’t hit a tree, and safety crews can get there quickly.”

But his hope for King County to relax its requirements on wetland sensitive areas is a serious issue for plan opponents, who call it a “special right” that other people don’t enjoy.

Tackling noise

Fiorito claims his plan efficiently cuts but does not eliminate noise leaving the property. In 2006, he said, he received permission to move the existing shifter kart race course from the southeast portion of the property to the central west portion and sink it 25 feet into the ground. This moved it farther away from the residential development to the east and cut down on the noise.

“The theory behind that is that if the noise off the kart course hits a berm before it hits the houses, there is going to be less noise reaching the houses than there was when it was on the same level as the houses and closer to them,” Fiorito said. “The housing development cropped up in the 70s, about 15 years after the track was built, so they should have a reasonable expectation of noise. Is it ever going to be completely inaudible? No. This is a race track. Ninety-nine percent of the people who live near the racetrack moved in after it was built, so they should expect some noise.”

Fiorito said that counter to what opponents have claimed, he has no plans to keep the track operating 24 hours a day. He also defended the county ordinance that would have a created a special overlay district for Pacific Raceways. It has been replaced by a process called a demonstration project.

“We’re certainly not shying away from an objective environmental review. I’ve been accused of crafting this proposed county ordinance to circumvent the (State Environmental Policy Act) process. That was never its intent, it was to set out a reasonable process with reasonable time frames associated with it and establish some baselines. We already have a track that exists here. I didn’t want to be analyzed as if I were proposing a brand-new activity out in a pristine forest somewhere. I wanted some recognition that we already exist and already create noise and traffic.”

About the CUP

One sensitive issue is the conditional use permit and the contention that he is in violation of it by operating on Mondays and Tuesdays and the one quiet day a month. He said the CUP does not exclude non-race testing. He said the precedent has been set over the past decades that muffled vehicles – such as the driving school that operates on Mondays and Tuesdays employs – are quiet and non-impacting and that they don’t raise the noise above the surrounding ambient noise level. He said, however, that he is willing to forego the use of the track by muffled vehicles on Mondays and Tuesday if he gets the plan approved.

“If I can replace that 30 percent of my income with income from the buildings and from professional racing events hosted on the race course, I can offer that up as a mitigation measure in terms of providing two days a week that have no noise at all emanating from the property.”

He said he’s not trying to slip anything by people, he just wants King County to treat him fairly.

“I think it’s undisputed that these things are huge economic engines,” he said. “We like to push the job opportunities that we are creating, not only with the racing surfaces but with the circa 1,000 jobs that we will provide with the commercial industrial park and the regional economic benefit of being able to host more national events than we can now. Each national event produces somewhere near $15 million worth of economic impact, and we have one now. If we have four events instead of the one we have now, based on the races alone we’re up to $60 million. If we are allowed to realize our vision, we could easily be responsible for a couple hundred million dollars worth of regional economic impact.”