They were aviation pioneers who fought discrimination at home and the enemy abroad.

Theodore “Ted” Lumpkin was an original Tuskegee Airman, an intelligence officer for the U.S. Army Air Corps’ first black combat unit, the “Red Tail” fighters, that helped conquer the skies over North Africa and Europe during World War II.

Elizabeth “Betty” Dybbro was an original herself, a volunteer in the Women Airforce Service Pilot (WASP), the first female outfit in history trained to fly American military aircraft during WWII. WASP pilots, who numbered just over a thousand, ferried planes throughout the country, hauled targets for shooting practice and performed other stateside duties to free up male pilots for combat.

Each was committed to duty despite race and gender inequality that was prevalent in the military in those days.

Decades later, members of the Tuskegee Airman and the WASP were finally recognized for their achievements. Members officially received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award from Congress.

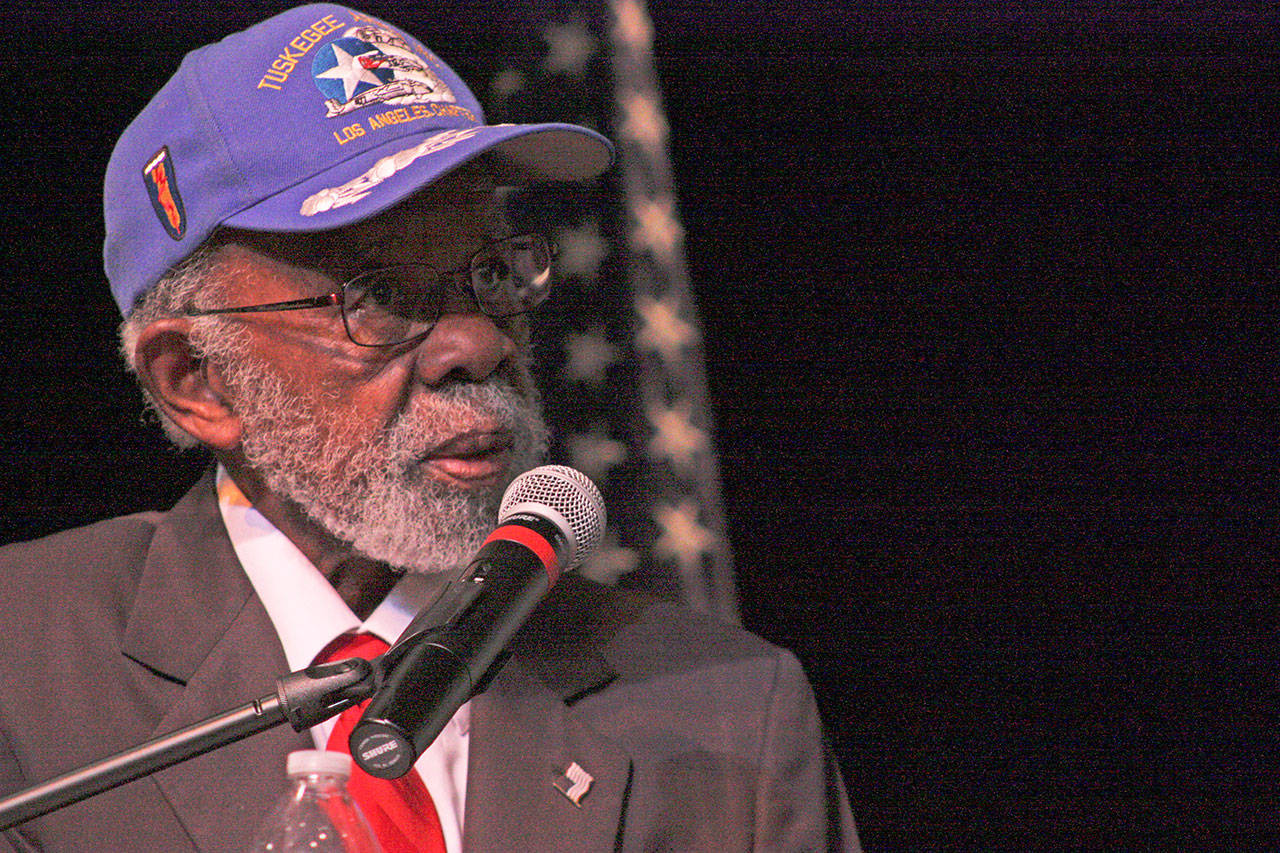

Lumpkin and Dybbro – nonagenarians who are active, healthy and engaging storytellers – were special guests at a Legends of Aviation program at Green River College on April 12. Each shared a chapter of their life story to students, aviators, historians and others gathered at the Mel Lindbloom Student Union Hall.

“I am honored and humbled to speak to you today,” said Lumpkin, 97, one of only a few hundred Tuskegee Airmen known to be living today. “Our legacy is important because we overcame a lot of obstacles and succeeded where we were expected to fail, and that was because we were well educated in most instances. …

“We changed the military. We changed the way blacks are regarded in this country.”

Only the best and brightest were selected for the first aviation cadet class in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1941. Lumpkin, who was too near-sighted to become a pilot, joined the brain trust. He served overseas in Italy during WWII as a member of the 100th Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group. The 332nd – along with the 477th Bombardment Group – was among the first African-American military pilot units.

Lumpkin was called upon to gather important information and report to command staff, providing vital details that helped squadrons pull off successful missions.

“I would brief the pilots before the missions, then debrief them when they came back,” he said. “When they didn’t come back, it was a very sad day,”

Lumpkin retired from the Active Air Force Reserves in 1979 with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

He returned to college, earned a degree at the University of Southern California and worked in administration for Los Angeles County before getting into real estate.

Lumpkin proudly looks back at his military service today despite the profound segregation at that time. The “Red Tails” became a respected fighter group that performed efficiently as attack squadrons and bomber escorts. The airmen paved the way for the integration of the country’s military.

“To represent what it does today to people is probably the most satisfying thing,” said Lumpkin, who is past president of the Los Angeles chapter of Tuskegee Airmen Inc. “People hand’t realized what we had done and what it meant to this country and to ourselves.”

Farm girl becomes a pilot

Dybbro grew up on a farm, never wandered more than 50 miles from home.

That all changed one day when she read a newspaper article calling for women to fly airplanes.

“I was adventuresome.,” Dybbro said.

Of the 25,000 women who applied for pilot school, only 1,900 were accepted. Dybbro was one of them.

She was one of the few who passed the training and spent 1944 as a WASP flying for the Army Air Force. During that time, she piloted many planes, including the B-26 Marauder and the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, while stationed at Nellis Air Force Base, near Las Vegas, Nev.

She recalled times when she flew a B-17 bomber, hauling targets for practice shooting.

“The fighter pilot had to play along and attack us,” Dybbro said. “There was this one pilot who sat on my wing … every day, every time I went out there he waved at me and flirted with me in the air.

“And you know what happened?” she said. “I married him.”

After the war, Dybbro enjoyed a good life, flying only occasionally.

Looking back, the 94-year-old Dybbro, who lives in the Olympia area today, was proud of being a part of women’s military history. Fascinated by aviation pioneers like Amelia Earhart before her, Dybbro and other women would became pioneers, too.

“I was lucky to be at the right age at the right time,” she said of her experience. “If (women) want to do something, then go out and just do it.”

The event was sponsored by the Green Tails Aviation Club, with support from the Green River College Foundation, Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Alaska Airlines, Western Region Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. and the Civil Air Patrol.