I like to wander through cemeteries.

There, it’s out.

Does that make me a weirdo? I don’t think so. But if I am, friends have assured me I am not alone — that I am part of a great company of weirdos.

For me, cemeteries are places for reflection, presenting me with tales told. And as I pass through life, of course I am bound to know more and more of the tellers.

That stone there marks the epilogue to a long ago tragedy, the story of a classmate of mine whose life was cut off by a car crash. Barely into his early teens, he would never grow older.

Under another stone lies a neighbor of my early boyhood. He was mere moments in Vietnam in 1969 when a single shot ended his promising life, and devastated his mother. I remember the day. She was his first child.

Over that rise is the golden boy, the phenomenal athlete of my neighborhood, gone much too soon. Under the single date on one barely visible stone is a baby whose eyes never opened on life.

As I wander and ponder the meaning of those human lives, I feel the weight of the past, shimmering in the heat of a high summer day.

Auburn pioneer Irving Knickerbocker lies under a small, sober stone, which marks only his name and the dates of his birth and death. I wonder what the city’s long seasoned attorney would think today of the community he served, now grown so large, whose name he was instrumental in changing from Slaughter to Auburn. A feat for which we can all thank him. The size of the stone seems to me a strikingly bald coda to a remarkable life.

When I think about Knickerbocker, I try to imagine the city of Auburn, spread out to the east below the cemetery hill, not as it is now, but as Knickerbocker and the others who lie in the cemetery would have known it in their days. About features of the landscape familiar to them that live now only in fading memories, or in grainy photos, or not at all.

I think about the thousand green, leafy places where a girl whose name I knew before her early death rode her bike, of the fertile fields where she picked berries, fields that have long since hidden their power of generation under development.

I remember visiting White Lake when I was a tiny kid. A tiny pocket of a lake, a marvel of crystal clear water and a beautiful sandy bottom, it was closed to swimming after a teenage boy drowned there in the summer of 1973. The lake is still there, though it’s been mostly out of public sight for nearly 50 years. The Muckleshoot Tribe owns the property today.

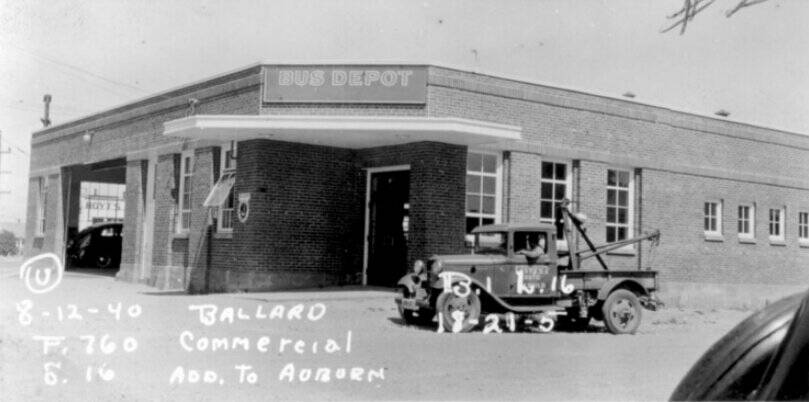

I remember, too, stepping out from Auburn Avenue Theater onto Auburn Avenue one night after watching “Darby O’Gill and the Little People.” I was suddenly curious about an abandoned building two blocks north. I asked my father about that building. Turns out it was Auburn’s first bus depot. Wells Fargo is there now. How many of the inhabitants of the cemetery relied on that long-vanished depot to get around?

Those features were part of the world many of them knew.

The feelings evoked by my cemetery wanderings are the same as described by Charles Dickens when he wrote of the inhabitants of Dingley Dell in the famed Christmas chapter of The Pickwick Papers:

“Many of the hearts that throbbed so gaily then, have ceased to beat; many of the looks that shone so brightly then, have ceased to glow; the hands we grasped, have grown cold; the eyes we sought, have hid their luster in the grave; and yet the old house, the room, the merry voices and smiling faces, the jest, the laugh, the most minute and trivial circumstances connected with those happy meetings, crowd upon our mind…”